Imagine navigating a busy city street, ordering food, or reading a prescription label—without seeing. For nearly 300 million people worldwide who are blind or have low vision, these challenges are part of everyday life. But thanks to advances in accessible technology, tasks like these are becoming more manageable. What tools are currently available? Are they truly meeting the needs of the communities they are meant to serve? And how might we design more intuitive alternatives for the future?

Why Language Matters

But before diving into the tech, let’s begin with a topic that is just as important: inclusive language. How we talk about blindness shapes how we think about it—and how we design for it. Many blind individuals don’t define themselves by what they lack. That’s why terms like visually impaired, visually challenged, or vision loss can be problematic. They emphasize what is “missing” instead of recognizing that blindness is a different way of experiencing the world. Some once thought the word blind was too blunt, but it simply states a fact—without negative tone. Phrases like “blind person” or “person who is blind” center the individual, not the disability.

Tools That Have Paved the Way

Humanity has been developing tools to support blind individuals for thousands of years. For example, Didymus the Blind, a 4th-century religious scholar from Alexandria is often depicted with a walking cane—one of the oldest tools that facilitates autonomous movement for blind individuals. Today, white canes guide blind individuals through their surroundings, often paired with tactile paving—yellow textured paths used in train stations or along sidewalks. Audio signals at crosswalks, activated by buttons, let users know when it’s safe to cross.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Didymus_the_blind.jpg

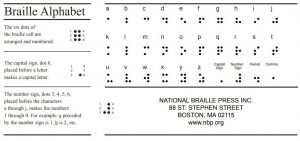

Tactile forms of reading also date back thousands of years. Didymus reportedly used carved wooden letters to learn to read and write – an early precursor of Braille. In 1824, Louis Braille developed the modern Braille system, using up to six raised dots arranged in a cell to represent letters, numbers, punctuation, and even musical or mathematical notation. His system was adapted from an earlier 12-dot code by Charles Barbier, and is now the universal standard for tactile reading and writing. In practice, Braille reading is generally somewhat slower than print reading, but essential for accessibility in public spaces, such as museums. In recent years, Braille literacy has declined as audio technology—such as screen readers, smartphones, and audiobooks—has become more widespread. Many smartphones now do support the Braille alphabet for composing text messages, helping to preserve tactile literacy in a digital format.

Source: https://primarysourcepairings.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/braillealphabet_npb-org.jpg?w=982

These tools are essential, but not always enough. Many modern household appliances have touchscreen-only controls with no Braille or audio support. Product labels, such as on shampoo or cleaning supplies, often lack accessible information. And though QR-code menus are more common, they’re still far from standard.

New Frontiers: AI Apps and Smart Canes

Thankfully, new innovations are offering more possibilities. Many AI-powered apps describe surroundings using a smartphone camera. Some connect users to sighted volunteers for real-time assistance. Others use AI to recognize objects, read text, or describe faces. However, currently, AI doesn’t always get it right. Relying on a smartphone app or an internet connection doesn’t always work in real-world crisis situations. What happens when your phone dies or you are in an area with no service? Assistance from sighted volunteers is often more reliable than AI, but not always available—and paying for professional assistance can add up quickly.

Meanwhile, smart canes are evolving. These tools now come with obstacle sensors, GPS, internet access, and built-in voice assistants. Users can access public transport updates, get step-by-step directions, and navigate complex environments—directly through the cane. However, these can also be expensive. Keeping costs down on technology and assistance is necessary for accessibility.

Designing with the Blind in Mind

Blind individuals fundamentally experience the world differently. They navigate space differently than sighted people, and they also talk about space differently than sighted people (Mamus et al., 2023). They break routes into smaller, manageable parts and rely on landmarks, rather than a map-like perspective. They also use an egocentric perspective—understanding the world based on their own body and movement. This has implications for how we design navigation tools.

For example, most current apps give directions like, “Walk straight until you reach the roundabout,” assuming visual reference points. But blind users benefit more from directions like:

“Walk ten steps forward until you reach a noisy intersection. Then turn right, toward 2 o’clock, keeping the tall hedge on your left.”. Therefore, to truly serve blind users, navigation apps must adapt to this different way of experiencing space. That means using more intuitive, body-centered descriptions.

Today’s technologies show great promise—but the future of accessibility isn’t just about new gadgets. It’s about rethinking design from the perspective of those who use it. It requires better research, more inclusive design teams, and a willingness to listen to the people we are designing for. It’s about building a world that works better for everyone, no matter how we perceive it.

Author: Ezgi Mamus

Editor: Jitse Amelink

Photo credit featured image: WeWalk

References

Bashin, B. (2024). Be My Eyes “Inclusive Language” Guide. https://www.bemyeyes.com/blog/be-my-eyes-inclusive-language-guide/

Mamus, E., Speed, L. J., Rissman, L., Majid, A., & Özyürek, A. (2023). Lack of visual experience affects multimodal language production: Evidence from congenitally blind and sighted people. Cognitive Science, 47(1), e13228.

Thomas, C. (2004). How is disability understood? An examination of sociological approaches. Disability & society, 19(6), 569-583.

Wetzel, R., & Knowlton, M. (2000). A comparison of print and braille reading rates on three reading tasks. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 94(3), 146–154.