What one child taught us about how we learn words

by Anna Mao

You’re out on a walk and see a cute pet in the grass in front of you. Immediately, you think, oh, a dog! Now stop and think for a moment: dogs come in many different shapes and sizes, and you may never have seen one like this before. So how did you know what you’re looking at is a dog? nd how come even a two-year-old could tell you the same thing? Where does this amazing ability to name what we see so quickly and accurately come from?

Born knowing or simply learning?

For a long time, scientists have been curious about how humans come to know that certain words refer to certain objects. To a new-born baby, hearing the word for the first time, “dog” could mean anything – the toy their mother is pointing at, the direction she is pointing in, the type of animal the toy is, or anything brown and soft. So how does that baby learn to determine accurately that dogs can look like Dalmations, chihuahuas, or huskies, but not bears?

Scientists have been divided on why we are able to learn words. Some believe that humans are born with a specific ability that helps us learn words. Some believe that our amazing ability to learn words develops together with more complicatedskills like logical reasoning. And some scientists believe that at the heart of our early word learning is a set of much simpler skills that do not require much prior knowledge at all. In other words, we learn language just like we learn many other things – by recognising that certain things go together, like the sun and warmth, or in this case, words and the things they describe. This is known as “associative learning”.

So what evidence do we have that associative learning is enough?

How a real child sees (and hears) it

One group of researchers came up with a novel idea – to record what a real child sees and hears, and to see if a computer program can learn words from just that footage using only simple associative learning.

Their study focused on data from one child named Sam, who wore a camera strapped to his head at different times from ages 6 to 25 months. Over a year and a half, Sam recorded 61 hours of video footage of things he saw and heard, including 37,500 times he spoke or people spoke to him.

Sam with the camera strapped to his head

Image source: Scientific American

To test if learning simple associations is enough for a child to learn a word, the researchers designed a machine learning program that kept track of what Sam saw through his camera and what he heard while looking at it. By combining the two and determining which objects and words were recorded at the same time, the program “learned” which words matched which objects.

Did the program learn words?

How can we tell if the program “learned” words like children do? By making it do the same tasks that a child can! After the program had sorted through all 61 hours of video, the researchers put its learning to the test: they displayed four different pictures taken from Sam’s video footage and asked the program to determine which of them matched a certain word.

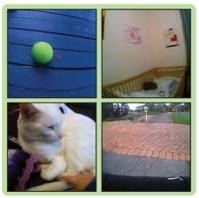

For example, researchers showed these four images and asked, “Which one is the ball?”

Image source: Science

The result? The program named objects it had seen before correctly about two thirds of the time . This may not seem like a lot, but it is about as good as another program which sorted through over 10,000 times more data – and while that program used more complicated steps, the new program based on Sam’s videos only used associative learning. Simplicity does the trick.

But did it really learn words?

Of course, just being able to match names and objects the child had already seen is not enough. If we really know what a dog is, we don’t just recognise dogs we’ve already seen, but all dogs. So to test if the program truly learned the words for objects, the researchers displayed pictures the child had never seen with unrealistic white backgrounds and asked the program to determine which one matched a word it had supposedly “learned”.

For example, which one of these is the ball?

Image source: Science

This time, the program made the right choice a third of the time. That is not very good, but still better than if it had chosen one out of four choices randomly. Associative learning may not be enough for a child to fully learn a word – but it’s a pretty solid start!

Of course, other skills and knowledge can contribute to early word learning – the program wasn’t perfectly accurate, and it struggled to name objects in unfamiliar scenes. Still, the simple skill of associative learning can be a good start.

Next time you see a cute dog, don’t take for granted that you know what it is. Your ability to identify it is quite incredible – though it may start out simpler than you think!

Credits:

Writer: Anna Mao

Editor: Jitse Amelink

Translation Dutch: Anniek Corporaal

Translation German: Carmen Ramoser

This article references the following paper: “Grounded language acquisition through the eyes and ears of a single child,” by Wai Keen Vong, Wentao Wang, A. Emin Orhan, and Brenden M. Lake. The full article can be found on Science here.