For example, I have heard many Australians declare “It’s freezing here!” when talking about winter Down Under, but a quick internet search shows that the average temperature in Sydney ranges between 9°C at night to 18°C during the day in its coldest month. As a Dutch person, I tend to take the equivalent Dutch verb vriezen a bit more literally, and vriezen implies sub-zero temperatures as it refers to the point at which water turns into ice. So those “freezing” winters in Australia always sounded a bit funny to me. The fact that we all like to talk about the weather and yet can experience it so differently makes our vocabulary for temperature an interesting part of language to study, so let’s have a look at what happens around the world.

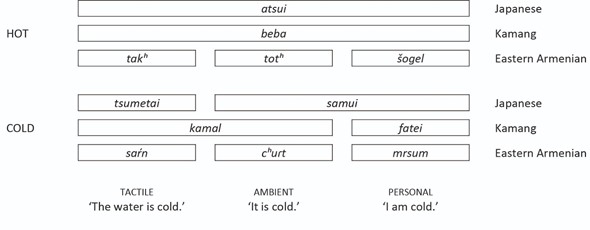

One thing that varies across different languages is what temperature words are used for. Take, for example, the phrases: “The water is cold/Het water is koud/Das Wasser ist kalt”; “It is cold/Het is koud/Es ist kalt”; and “I am cold/Ik heb het koud/Mir ist kalt”. English, Dutch and German use the same temperature word in each phrase: English cold/Dutch koud/German kalt. Japanese speakers, though, would use tsumetai for the water and samui in the other two scenarios. This is because they make a distinction between something that is cold to the touch and a type of cold that is not related to touch. Speakers of Kamang (a Papuan language spoken on Alor Island in Indonesia), on the other hand, single out the personal feeling of cold (faatei) and use a non-personal word in the other two scenarios (kamal). Interestingly, when Japanese and Kamang speakers talk about “hot”, they do not make these same distinctions and use a single word for all three scenarios instead (Japanese atsui1; Kamang beba). Clearly there can be differences between opposite ends of the temperature scale as well. That is definitely not the case in Eastern Armenian, however, where there are different words for all three scenarios for both hot and cold!

As the examples above show, languages can differ quite a bit in how many temperature words there are, but things can really get out of hand quickly when you want to count all the different types of expressions that use temperature words—think of English freezing cold, biting cold, scorching hot, sweltering hot. Many languages have special terms for extremely hot that are associated with the sun and fire, or ice and freezing for extremely cold temperatures. However, such complex and often metaphorical expressions do not teach us much about the more basic temperature levels that most humans (and human languages) differentiate between. It seems that there are generally four basic levels of temperature expressed in various languages: cold – cool – warm – hot. Some languages distinguish all four (like English, Dutch, German and Japanese). Languages with three levels group cold and cool together (like Finnish and Indonesian). Commonly however, there are just two levels: cold/cool versus warm/hot (as in Kamang). But as we saw earlier, within each level, languages can still have different words for different temperature types (that is for touch, personal feeling, or ambient temperatures) as explained above.

All of these examples show that the way people talk about temperature–something that seems pretty straightforward–can vary quite a lot between different languages. Not only do languages distinguish between various temperature levels, some also take into account different types of temperature. Interestingly, many languages use temperature words in figurative expression as well, which gives us even more things we can use them for–and thus more ways in which languages can differ. For example, English uses “cold-blooded” for people that are cruel and show no pity, but when people are called “cold-blooded” in Kamang it means they are amicable and friendly. And while you can feel good about a nice compliment when your boss calls you a ‘warm’ person, you wouldn’t want them calling you ‘hot’. So, always keep a cool head when you’re talking about temperature.

Notes

1 The difference is not present in spoken language, but Japanese writing does have different characters for tactile hot (熱) as opposed to non-tactile hot (暑).

Further reading:

Koptjevskaja-Tamm, M. (Ed.). (2015). The Linguistics of Temperature. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Writer: John Huisman

Editor: Natalia Levshina

Dutch translation: Elly Koutamanis

German translation: Ronny Bujok

Final editing: Eva Poort, Merel Wolf