What was the main question in your dissertation?

My dissertation examined two main questions: (1) Is it easier to process spoken or written language? (2) Can you process language better if you are a real bookworm and read a lot?

Can you explain the (theoretical) background a bit more?

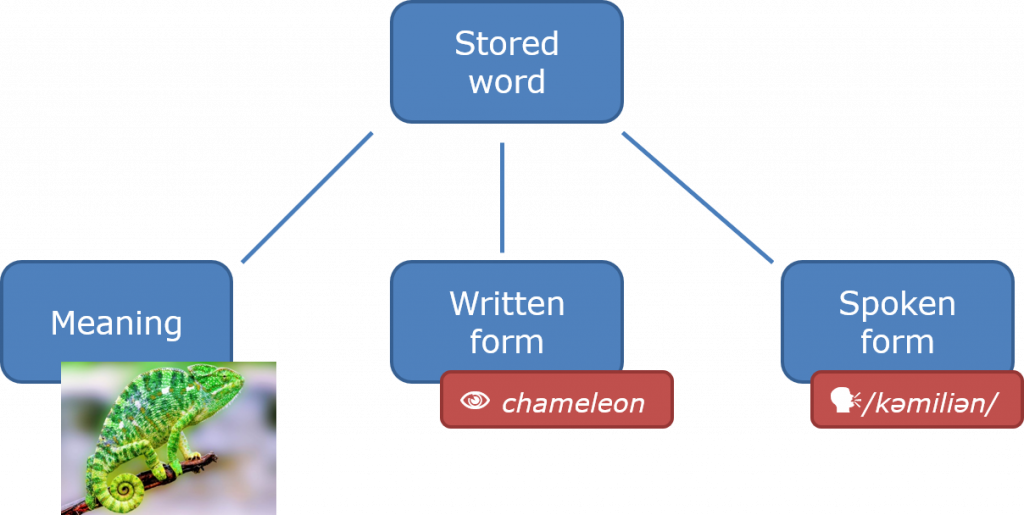

Language has different forms or modalities: the spoken form you hear during a conversation and the written form you encounter when you read. The way language is stored in our heads can be thought of as a kind of mental dictionary with a lemma for every word we know. Such a lemma, for example, for the word chameleon, contains information about both modalities (see Figure 1). So in addition to the meaning of a word (a distinct sort of lizard), we also store information on how to write (with ch and two e’s) and pronounce (/kəmiliən/) that word. However, we don’t always store those different bits of information very well. For example, you may know what a chameleon is and how to write the word chameleon, but not how to pronounce it. This also affects how well you recognize a word. For example, you might easily recognize the written form of chameleon, but have to think for a moment when someone says ”/kəmiliən/”.

Related to the question about the interaction between language processing and reading behavior, it is important to note that people vary greatly in their language skills. Not everyone can write or speak equally well. The idea is that, like any other skill, you get better as you practice. I was wondering if it matters what form of language you come into contact with. Can reading a lot of written language also improve your general language skills? And does this affect your spoken language skills?

Why is it important to answer this question?

The question about the interaction between written and spoken language processing is interesting because so far they have mostly been studied separately.

The research on reading and language proficiency has practical relevance. There is a huge dip in the language skills of Dutch youngsters and there is increasing reading literacy. Fewer and fewer books, newspapers and magazines are being read. Encouraging reading may be able to remedy the decline in language skills. Research can further motivate this proposal.

Can you tell us about one particular project? (question, method, outcome)

In Chapter 3, I examined how accurately and how quickly people could recognize spoken or written words. Subjects were shown or told easy (“alligator”), difficult (“polemology”) and non-existent words (“garidine”) and had to decide as quickly as possible whether they knew the “word” or not. Both easy and difficult words were recognized equally accurately in written and spoken form. Subjects were faster at recognizing written words than spoken words, though. This in itself makes sense because people can read faster than it takes to pronounce (and listen to) a word. There was a greater difference between the written and spoken form for easy words (0.6s) than for difficult words (0.4s). Why this is the case we do not yet know exactly, but it does show that the effect is not only caused by the fact that reading is faster than listening. The effect would be the same for easy and difficult words.

What was your most interesting/ important finding?

We found that you can recognize written and spoken language equally accurately, but that you can process written language faster. We also found that bookworms can indeed process, understand and produce language better than people who don’t read much. It seems to be the case that reading causes the bits of information about a word to be stored better and more accurately. As you encounter a word more often, you become increasingly familiar with exactly what it means, and how you write or pronounce it. Because the word is better stored, you can also recognize it more quickly when you encounter it again. So reading improves your language skills.

What are the consequences of this finding? How does this push science or society forward?

The conclusion that people recognize written and spoken words equally well, but recognize written words faster, comes in handy when designing language tests or vocabulary tests, for example. Given declining language skills, literacy and the problem of low literacy in the Netherlands, findings on the influence of reading behavior on language skills are also very relevant. For example, the government has recently called for a reading offensive to combat illiteracy. This research proves that reading behavior does indeed have a positive influence on language skills and thus validates policies aimed at promoting reading.

What do you want to do next?

I now work as a researcher at the Expertisecentrum Beroepsonderwijs. There I conduct research into all kinds of questions about education, commissioned by the government or schools. For example, these are projects about which interventions secondary schools can carry out to improve the language skills of their students or how the teacher training for elementary school teachers should be designed. In this job, I also have more time to disseminate and communicate the knowledge we gain from research.