What was the main question in your dissertation?

The main focus of my dissertation was to investigate children’s reasoning and communicating about spatial relations, i.e. the terms we use to describe how objects are situated in relation to each other. For instance, when we think of the set up of a plate and a spoon on a dining table, we can say that the spoon is to the right of the plate. In my dissertation I was interested in ‘How do children develop the ability to communicate and remember spatial relations between objects?’ and ‘Which factors influence this development?’

Can you explain the (theoretical) background a bit more?

Historically, research on how we talk and think about spatial relations has focused on speech only. While these studies have looked at differences between spoken languages, little is known about the effects of other possible variations in language acquisition situations such as exposure to multiple forms of communication (e.g., speech and gestures).

The focus on spoken languages prevents us from getting a broader picture of spatial language development and cognition. In my PhD project, I therefore aimed to go beyond previous work in understanding how people develop their ability to talk about and understand spatial relations, as well as how they remember information about spatial relations. I looked at both spoken and signed language and compared signers who were introduced to sign language early or later on in life as two new angles.

Why is it important to answer this question?

First, looking at different forms of language is important, because speaking children do not only get exposed to speech but also observe co-speech gestures, hand movements that accompany the speech, in their language input. Deaf children, on the other hand, acquire sign languages that are expressed solely visually. Spatial relationships between objects (e.g., the fork is to the left of the plate) are expressed quite differently in speech compared to gesture and sign. However, to date, little is known about whether using sign, speech, or co-speech gestures can shape the development of spatial language and its relation to cognition differently for signers and speakers.

Second, considering variations in when children are familiarised with sign language is important, as only 5% of deaf babies have deaf parents. These babies are highly likely to have seen their parents use sign language from birth and will be considered as a native signer. However, in most cases, deaf babies have hearing parents. Most likely, these kids – “late signers”- will only get introduced to a sign language at about around 6 years of age when they start going to a school for the deaf. Such cases are especially prominent in non-western countries such as in Turkey, which is the specific context of the data reported in my thesis. However, we do not know how differences in the timing at which children are introduced to sign language affects how they learn to talk about spatial relations and how it relates to their thinking.

Can you tell us about one particular project?

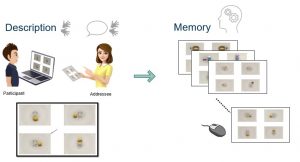

In one of my projects, deaf native and late signers of Turkish Sign Language (children and adults) saw sets of four pictures featuring the same two objects in a different spatial configuration (e.g., a fork left of the plate, a fork on the plate, etc.). They described one of these pictures – indicated by an arrow – to a deaf addressee. The addressee then selected the described picture from a set of pictures presented on a tablet. Later, participants engaged in a surprise memory task where they had to select the picture they had described previously.

I wanted to know whether late introduction to sign language influences the way late signers describe spatial relations between objects. Furthermore, I wondered how differences in how they describe spatial relations on the one hand and the timing of exposure to sign language (early or late) on the other predict further differences in their ability to remember spatial information accurately.

What was your most interesting finding?

The age at which you come into contact with sign language influences how often and in what way you express Left-Right relations between objects. However, it does not necessarily affect how well you remember these relations.

What are the implications of this finding? How does this push science or society forward?

Current findings have implications for developing intervention programs for deaf children with hearing parents before they come into contact with sign language. Deaf children’s access to a sign language must be considered a fundamental right. Nevertheless, in many cases, this right is not granted to them. Findings obtained from the current thesis have the potential to provide evidence to inform the decisions of policymakers and educators in some respects.

What do you want to do next?

I am currently running an intervention program that helps expose deaf children with hearing parents to a sign language before starting the school for the deaf. This research is funded by the SRCD Early Career Research Grant. Through this grant, I have developed an online application that allows me to follow their language development. This program and the obtained research output will allow me to document the importance of early sign language exposure for the development of linguistic skills.

Interviewer: Caitlyn Decuyper

Editor: Christina Papoutsi, Sophie Slaats

Translation: Julia von der Fuhr, Barbara Molz