What was the main question in your dissertation?

Generally, I am fascinated by the question of whether language affects the way we think about the world around us. In my thesis, I studied the effect of language on our perception and memory of everyday events, such as going for a walk or chopping vegetables.

Can you explain the (theoretical) background a bit more?

Our daily lives are full of events, from taking a shower in the morning to reading a book before bed. We experience these events directly, but also indirectly through language. What we hear, read, or tell others about events influences how we think about them and what details we focus on.

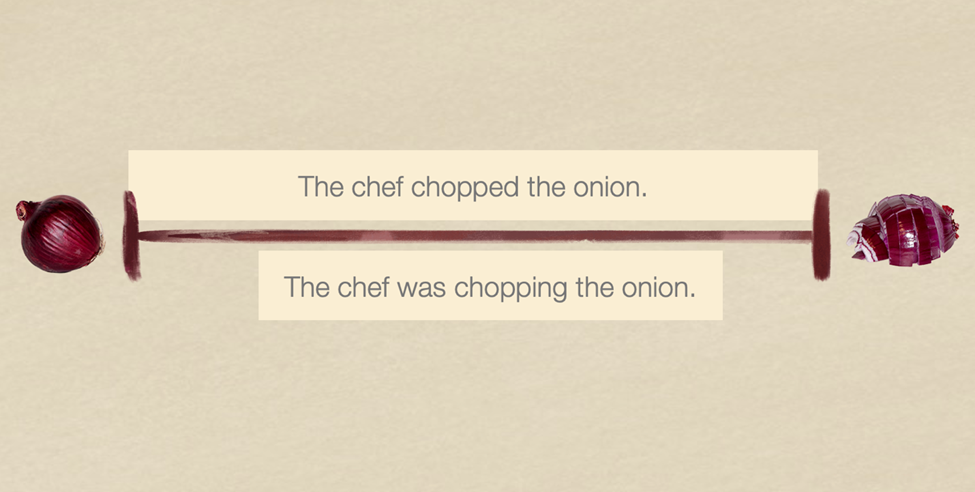

Events always have a beginning and an end (event boundaries). Time can frame an event and give it structure. Time can also be found in language in a variety of ways. In my PhD project, I specifically looked at the role of grammatical aspect, which can be used to offer a viewpoint on a situation. For instance, the chef chopped the onion and the chef was chopping the onion both refer to an event sometime in the past. However, chopped presents the event as completed, whereas was chopping describes the event as ongoing, with no particular focus on the boundaries or endpoint.

Why is it important to answer this question?

The core question of my thesis was whether grammatical aspect (chopped vs was chopping) guides the focus to event boundaries, and specifically endpoints. I wanted to investigate whether grammatical aspect can affect what people expect an object to look like when they read about an action event.

In several of my projects, I studied how language affects the way we picture objects being irreversibly changed by an action – like in the example The chef chopped/was chopping the onion. Research shows that when we read a sentence suggesting an object looks different after an action (She peeled the banana, suggesting the fruit is no longer in the skin), we also react faster to a picture of the changed object (a peeled banana) compared to a picture of the object in its original state (an unpeeled banana). So, the verb used –peel or chop– matters for how we think about the object. Grammatical aspect could have a similar effect on people’s thoughts about an object’s state: we may more easily picture a chopped onion after reading The chef chopped the onion, which has an endpoint focus (see image above), compared to The chef was chopping the onion, where the change is still in progress. If grammatical aspect can modify which details we deem relevant in an event, it affects how we think of the objects or people in events, how we describe who does what to whom, and what we remember about the event.

Can you tell us about one particular project? (question, method, outcome)

I looked at brain activity during picture presentation. English-speaking participants read sentences like The chef chopped the onion or The chef is chopping the onion word by word. After reading the sentence, they saw a picture of the object either in its original state (a whole onion, representing the beginning of the event), or in a changed state (a chopped onion, representing the end of the event).

Overall, the changed state pictures were perceived to better match the sentences compared to the original state ones, likely because the verbs described an event where objects are visibly changed.

The original state pictures were processed similarly well after both sentence types (was chopping vs chopped). However, grammatical aspect did matter for how well the changed pictures were integrated with the sentences. When reading chopped, signalling a ceased event, people perceived the changed picture to better match the sentence compared to when they read was chopping. So grammatical aspect guided event understanding such that the endpoint of the event (changed state of the object) was activated.

What was your most interesting/ important finding?

To me it was really interesting to see how grammatical aspect can affect how we understand events, but that it does not necessarily do so at all times. As you can read in the previous section, we found a subtle effect of grammatical aspect on how people expected the object to look. Perfective aspect (chopped) seems to guide our focus to the endpoint, which shows up in the brain activity prior to decision making. However, this aspect effect was not observed in a follow-up study, where we looked at the same sentences and pictures together with conscious decision-making (measuring reaction times).

It seems that grammatical aspect is showing an effect only under certain circumstances –at least when it comes to English.

What are the consequences/ implications of this finding? How does this push science or society forward?

Languages and their use are diverse and there is still a lot to uncover! Understanding how language use and language background shape our understanding of the world can have a wider-reaching impact beyond the lab. In my view, the way to go is to use a systematic way of looking at how expressions of time in different languages lead people of different language backgrounds to focus on event details and remember events.

What do you want to do next?

During my time as a PhD student, I was involved in several representational activities, for instance, as a member of the PhDnet steering group, local PhD representative, and deputy equal opportunities officer. Throughout the years these experiences have made it clear to me that –while I was really passionate about my research projects and psycholinguistics– I thrive best in support and representational roles in academia. After my MPI contract, I started as Policy and Communications officer at CLARIN ERIC. CLARIN is a European research infrastructure with an open science agenda that offers access to language data and tools for the social sciences and humanities. In my job, I develop the CLARIN strategy, am actively involved with several governance bodies, work on our equality plan and also do a lot of communications activities. It is a varied job in a great team, and of course language-related!